The first Micro Four Thirds collaboration was the Panasonic Lumix G Leica DG Summilux 25mm f/1.4 (MSRP $629.99), one of the widest-aperture first-party lenses available for the system (exceeded only by the eye-wateringly expensive Nocticron 42.5mm f/1.2).

While it looks the part of a classic "fast fifty" and is capable of some truly excellent shots, it makes its home in an increasingly crowded—and increasingly competent—part of the Micro Four Thirds lens library. The question is, can it stand up to the competition?

Who's It For?

In the film days, most SLRs were sold with prime lenses, not zooms. In part, that was because zooms were less common and more difficult to manufacture, but primes also offer superior image quality on the whole. The most common "kit" prime lens was a 50mm of some kind, because it's a do-it-all focal length that suits a variety of common shooting scenarios—portraits, landscapes, reportage, and street photography among them.

The Panasonic 25mm f/1.4 is the Micro Four Thirds equivalent; thanks to Micro Four Thirds' 2x "crop factor," a 25mm lens on a M43 camera behaves like a true 50mm lens would on a 35mm or full-frame digital camera. In addition to its fixed-yet-flexible focal length, this lens also provides a bright f/1.4 maximum aperture that affords superior low-light results and can create creamy-smooth out-of-focus backgrounds when shooting subjects up close and personal.

It might not be an ideal focal length for portraits, but it can snap them if that’s what you need. It's an excellent foundation for any Micro Four Thirds owner's lens collection, and it functions expertly on both Panasonic and Olympus Micro Four Thirds cameras.

Since it uses the Micro Four Thirds mount, the Summilux 25mm f/1.4 is compatible with both Panasonic and Olympus cameras.

At $600, it's a good deal more expensive than "fast fifties" from big brands like Canon and Nikon. It's also a good deal pricier than the Olympus 25mm f/1.8, which is just two-thirds of a stop slower but costs only $400. The Pana-Leica Nocticron 45mm f/1.2 is the only lens in Panasonic’s lineup with a wider aperture, but it's a more specialized lens primarily intended for portraits. It's also way more expensive and way bigger, and we wouldn’t recommend it to complete novices no matter how awesome it is (and boy is it ever awesome).

Look and Feel

While the Summilux 25mm f/1.4 is undoubtedly an optically impressive lens, we’ve always been a little disappointed with its build quality and design. Though popular DSLR makers may offer even cheaper-feeling fast fifties (looking at you, Canon and Nikon), Micro Four Thirds users are accustomed to a higher standard of build quality. This lens just pales in comparison.

The super-wide f/1.4 maximum aperture makes this lens bulkier and heavier than the competing Olympus 25mm f/1.8.

Even compared to other, more recent Panasonic/Leica collaborations, the 25mm comes up short. The Nocticron and petite 15mm f/1.7, for example, feature all-metal exteriors and aperture rings. With this 25mm, you get a plastic shell, a gummy rubber-coated focus ring, and a cheap plastic hood. Olympus, meanwhile, offers a range of jewel-like all-metal primes with nifty focus clutch rings. Again, this 25mm has nothing like that.

In the box, you get a branded pouch, lens caps, and the aforementioned plastic lens hood. Despite its chintzy build the hood has a distinctive square shape, which we think looks pretty sharp. The lens itself quite a bit bulkier and heavier than the competing Olympus 25mm f/1.8, which also has a lightweight plastic exterior and a metal mount. Mostly, that's down to the extra two-thirds stop of aperture.

The squared-off lens hood looks great, but it's a bit less robust than what you get with other Pana-Leica collaborations.

But looks aren’t everything. As mentioned, this lens is the second-fastest first-party option for M43, and the fastest 50mm equivalent lens with autofocus. As such, it doesn't have a lot of direct competition.

{{ photo_gallery name="Tour" }}

Image Quality

Like most "normal" primes, the Panasonic Leica 25mm f/1.4 doesn't have to make many optical compromises. These lenses are some of the simplest to design, and the result is usually minimal distortion, few aberrations, and high sharpness. The Summilux 25mm is no exception.

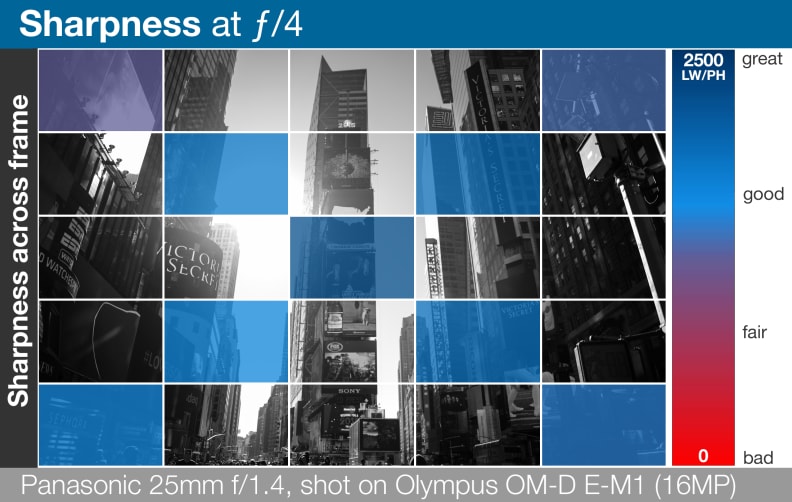

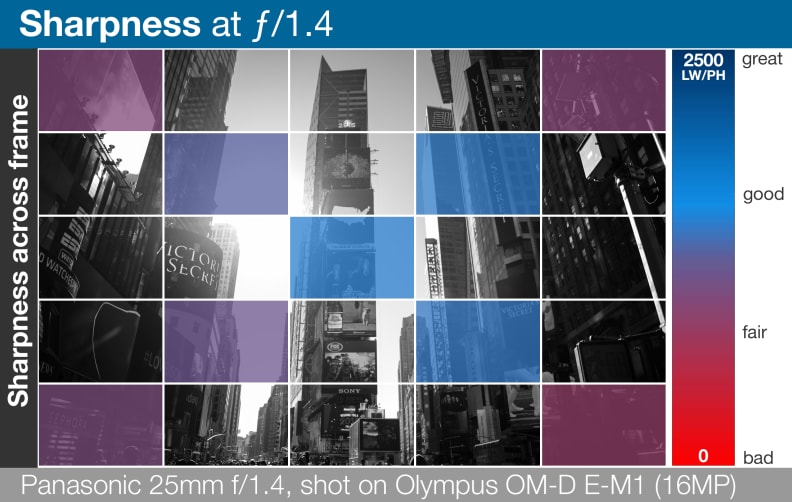

In our lab tests, we found that the lens is sharp enough at f/1.4, but truly excels from f/2.8 to f/5.6 in the center of the frame. Even tiny details are accurately captured, and you can expect sharp results through to f/8 and f/11, before diffraction begins to take its toll.

EXIF: 25mm, ISO 400, 1/50, f/2.8

The only major issue we found was corner performance. While it's quite good from f/2.8 to f/8, it's not nearly as exemplary as the center. At f/1.4 it's noticeably soft, so we wouldn't try shooting landscapes or other "flat" subjects wide-open; better to stick to portraits and other shots where lousy edge performance won't matter.

Test shots showed almost zero geometric distortion, meaning straight lines will stay straight in your photos. Chromatic aberrations were pretty well-controlled, as well, barely reaching "minor" levels at worst. You may notice it in some particularly high-contrast scenes, but it can be easily edited away.

EXIF: 25mm, ISO 400, 1/500, f/1.4

In real-world shooting, we found the lens's few technical issues weren't practical concerns. At f/1.4 we were more likely to fill the corners with out-of-focus background elements anyway. And while the backgrounds can look quite busy by f/2.8 (with occasionally "geometric" bokeh), at f/1.4 they have the buttery smooth quality you dream of in a fast prime lens.

Ultimately, this is a lens that could happily serve as the cornerstone of your Micro Four Thirds kit. At its best it's one of the sharpest lenses we've seen in this lens system. While that performance doesn't extend all the way to the corner, it's good enough.

EXIF: 25mm, ISO 400, 1/60, f/1.8

Below you can see sample photos taken with the Panasonic Lumix G Leica DG Summilux 25mm f/1.4 mounted on a Panasonic Lumix GH4. Click the link below each photo to download the full-resolution image.

{{ photo_gallery name="sample-photo" }}

Conclusion

If you do a lot of shooting in dim light, love beautifully blurred backgrounds, and want a lens that's far sharper than your kit zoom but still offers a bit of flexibility, look no further. This is a stellar example of the classic "fast fifty" that can do wonders for pros, enthusiasts, and newbies alike.

That said, there are a couple of less expensive lenses that offer 90% of the experience you'd get from the Summilux 25mm f/1.4 for a fraction of the money. We’re more likely to recommend those if you’re new to Micro Four Thirds, as you can dedicate more of your budget to even more lenses. (Always a plus!)

On the Four Thirds sensor, 25mm is equivalent to a 50mm lens on film or a full-frame sensor.

The Panasonic Lumix 20mm f/1.7 is in the same ballpark in terms of focal length, and has just a slightly slower f/1.7 aperture. It has a similar plastic build quality, but it’s also a lot more compact and portable. We’re also big fans of the Olympus 25mm f/1.8. Again, it's a tiny, lightweight, plastic lens, but it's also quite sharp and produces solid bokeh of its own. It’s $200 less expensive, and bright enough for all but the most demanding users.

But if you expect a lot from your lenses, the Panasonic Leica 25mm f/1.4 delivers where it counts. We’ve shot with it quite often since it was introduced in 2011, and it's never let us down, combining clinical brilliance and wonderful creative potential. For that reason, it's one of our go-to lenses for shooting product photos at poorly-lit trade shows.

Unless you're shooting subjects that demand an extremely short or very long focal length (architecture, sports, wildlife), this is a lens that can rise to the occasion. It won't leave you wanting. When evaluating any lens, we focus on four key areas: sharpness, distortion, chromatic aberration, and bokeh. A perfect lens would render the finest details accurately, wouldn’t distort straight lines or produce ugly fringing around high-contrast subjects, and would create smooth out-of-focus areas.

The Panasonic Leica DG Summilux 25mm f/1.4 approximates the classic "fast fifty" 50mm f/1.4 full-frame lens for the Micro Four Thirds system. It's an important cornerstone for the mount family, and a very solid one indeed. Sure, corners are a little softer than we'd like from f/1.4 to f/2.8, but the tack sharp center performance and lack of optical aberrations makes this an excellent addition to any Micro Four Thirds camera.

Sharpness

A lens's sharpness is its ability to render the finest details in photographs. In testing a lens, we consider sharpness across the entire frame, from the center of your images out to the extreme corners, using an average that gives extra weight to center performance. We quantify sharpness using line widths per picture height (LW/PH) at a contrast of MTF50.

The best results come from stopping down to f/4.

While not quite a match for the best 50mm f/1.4 full-frame lenses, the Summilux 25mm f/1.4 does quite well for itself at most apertures. The center performance is excellent everywhere, hitting roughly 1,450 lines at f/1.4 and skyrocketing up over 2,150 lines from f/2.8 to f/5.6—superb for Micro Four Thirds. It tapers off through the rest of the aperture range, falling back to the 1,400s at f/11 due to diffraction.

In the midway areas (50% from center) the 25mm f/1.4 doesn't achieve the same lofty heights, going from 1,300 lines at f/1.4 to 1,800 lines at f/4 and falling back to 1,350 lines by f/11.

At full wide, softness creeps into the corners of your shots.

The corners are the only real trouble spot. At f/1.4 they manage just 975 lines—pretty soft. This jumps to a more respectable 1,150 lines at f/2 and hovers around 1,400 lines from f/2.8 through f/8. It's not the corner-to-corner sharpness that you get with some of the best fast primes out there, but most of those are simpler f/1.8 designs. Like most f/1.4 lenses you get improved bokeh in exchange for a little worse corner performance wide open.

Distortion

We penalize lenses for distortion when they bend or warp images, causing normally straight lines to curve.

There are two primary types of distortion: When the center of the frame seems to bulge outward toward you, that’s barrel distortion. It's typically a result of the challenges inherent in designing wide-angle lenses. When the center of the image looks like it's being sucked in, that’s pincushion distortion. Pincushion is more common in telephoto lenses. A third, less common variety (mustache distortion) produces wavy lines.

The 25mm f/1.4, like most normal primes, handles geometric distortion with aplomb. We recorded just 0.25% barrel distortion, which is virtually impossible to distinguish in an actual photograph.

There's always the question of whether Micro Four Thirds cameras apply some kind of distortion control, even in RAW shots. But given the focal length in question here, if here is latent distortion being corrected in-camera, it's minor enough that it doesn't concern us.

Chromatic Aberration

Chromatic aberration refers to the various types of “fringing” that can appear around high contrast subjects in photos—like leaves set against a bright sky. The fringing is usually either green, blue, or magenta and while it’s relatively easy to remove the offensive color with software, it can also degrade image sharpness.

In our test shots, we recorded minor CA (at worst) throughout most of the frame. It's not completely inconsequential—there's some magenta fringing visible in high-contrast scenes and in focus transition areas that you should be aware of. It's most noticeable at f/1.4, but even at its worst it's easy enough to correct.

Bokeh

Bokeh refers to the quality of the out-of-focus areas in a photo. It's important for a lens to render your subject with sharp details, but it's just as important that the background not distract from the focus of your shot.

While some lenses have bokeh that's prized for its unique characteristics, most simply aim to produce extremely smooth backgrounds. In particular, photographers prize lenses that can produce bokeh with circular highlights that are free of aspherical distortion (or “coma”).

EXIF: 25mm, ISO 100, 1/125, f/1.4

In general, the Leica 25mm f/1.4 produces wonderful bokeh at f/1.4, with backgrounds becoming smooth washes of color that help isolate your in-focus subject. Even busy, high frequency backgrounds are smoothed out so they don't distract too badly. The photo below is a worst-case example of how "nervous" the bokeh can get.

EXIF: 25mm, ISO 400, 1/50, f/2.8

There's some noticeable coma toward the corners of the frame. While at times this can give your scene a painterly look, it means the lens isn't ideal for shooting stars or other scenes where you want to preserve circular points of light. These specular highlights tend to become quite polygonal once you stop down to f/2.8, which gives background a more unnatural, geometric appearance—not ideal, but not a deal-breaker, either.

Meet the tester

Brendan is originally from California. Prior to writing for Reviewed.com, he graduated from UC Santa Cruz and did IT support and wrote for a technology blog in the mythical Silicon Valley. Brendan enjoys history, Marx Brothers films, Vietnamese food, cars, and laughing loudly.

Checking our work.

Our team is here for one purpose: to help you buy the best stuff and love what you own. Our writers, editors, and lab technicians obsess over the products we cover to make sure you're confident and satisfied. Have a different opinion about something we recommend? Email us and we'll compare notes.

Shoot us an email