Down vs down alternative: it's not just a load of fluff

From cleaning to pros and cons, here's everything you need to know about the stuff filling your bedding.

Products are chosen independently by our editors. Purchases made through our links may earn us a commission.

I am the designated sleep person here at Reviewed, but sometimes I still find myself overwhelmed thinking about all the variables and materials involved in bedding alone. (Don’t get me started on mattresses!) Perhaps two of the most mystifying materials are down and down alternatives—because they're usually encased in pillows or comforters, the differences between them are hidden to the eye.

But have no fear, I’m here to shed some light on the part of your blanket, jacket, or even sleeping bag, for that matter, that never sees the light of day.

What’s down?

Down is an insulating layer that provides ducks and geese protection from water and the elements. You can’t see it on fully grown birds as it’s beneath the visible feathers, but you’ve probably seen it on baby geese and ducklings, which have only down for a period after hatching. (It’s not harvested from baby geese or ducklings though, but there’s more on ethical down below.) Unlike feathers, down grows in spindly fluff clusters and lacks a central shaft—part of what lends it that classic cushy and forgiving sensation.

Down is a popular material in bedding and winter clothes for a number of reasons. It has a higher “warmth-to-weight” ratio than other materials, which means that it generally takes less weight in down to make you warm than it would, say, feathers. It’s also compressible, which can make down garments, like jackets, easy to travel with, says Jamie Ueda, Reviewed’s apparel writer and textile expert.

There are different types of down, and some are more expensive than others. Goose down is considered better (and is costlier for it), because the clusters are larger. Mature birds also yield better down because the fibers aren’t as fragile as those in the down of younger birds.

Sometimes the same manufacturer will use different types of down for different products. Take Brooklinen. Its all-season down comforter has Canadian duck down, but the ultra-warm down comforter is stuffed with Hutterite down, which is sourced from Hutterite communities in Canada (a religious group that share roots with the Amish), and is higher quality, according to a customer service rep from Brooklinen. Further, the brand’s lightweight down comforter uses “recycled down”—it’s sourced from used products and cleaned, to the point that it’s “cleaner than virgin down,” says Katie Elks the director of design and product development at Brooklinen. Some down is inherently more expensive, so sourcing different types can make it possible to offer down products for cheaper—but spoiler alert: Cheaper is often still expensive when it comes to down. (The Brooklinen down comforters range in price from $249 to $499 for a queen size.)

Aside from cost, down has one other major downside: limited washability. Down products often require dry cleaning, as washing can make down less fluffy and warm. There’s also a notion that down is worse for allergy sufferers. While it’s somewhat true, it’s not necessarily because of the material itself (unless you are, in fact, allergic to down and feathers). Instead it’s because it isn’t easily washable to remove dust and dust mites (or folks aren’t fastidious enough). “The main thing that actually creates allergens is infrequent washing or not using a duvet cover to wash more easily,” Elks says.

What is down alternative or synthetic down?

From the name, you probably guessed that down alternative is a fill that’s akin to down and mimics the sensation, but isn’t made from goose or duck fluff. It’s popular because it offers similar characteristics at a lower price. But this fill isn’t as clear-cut as down because there are numerous potential materials and sources.

Some manufacturers, like Brooklinen, Nectar, and Buffy, make down alternatives from recycled products, like plastic bottles. The fill used in Brooklinen’s lightweight down-alternative comforter is made with made from repurposed plastic. The plastic is first converted into pellets, which are then “melted down and turned into polyester yarns, which get cut into small lengths to mimic down clusters and create a lightweight fluffy fill,” Elks says. (Brooklinen’s down alternative comforters range from $199 to $299 for a queen size.)

Land’s End falls on the other end of the spectrum. It manufactures the down alternative for its comforters—no recycling involved. But the range of materials used to produce down alternative means quality can really vary, Ueda says.

Warmth and heaviness also vary across down alternatives. Generally, it takes more weight and bulk to achieve greater warmth as compared to down, Ueda says. This be a positive and a negative, depending on individual preferences and the product at hand, “in a coat, this would be a con as the coat will be heavier, but in a blanket this could be a pro if someone prefers the light pressure of a heftier blanket,” she says.

Down alternative can be a great choice for allergy sufferers as it’s generally easier to launder, and the fill can withstand more frequent care better than down can, Elks says. Far more down-alternative comforters can be tossed in the washer at home and tumbled in the dryer.

What about feathers?

Feathers used in bedding are some of the same feathers that are visible on ducks and geese. Birds need them for flight and general protection, but they tend to offer limited insulation. There are a couple types of feathers: flight feathers, which are flat and considered lower quality and may be chopped up in cheap bedding; and body feathers, which tend to cost more than flight feathers, but less than down.

Some products use a mix of feathers and down. In a pillow, the blend will provide more support, Ueda says. It also tends to lower the price, which can be an upshot for consumers.

One of the biggest downsides of feathers? Unlike down, they have a pointed and rigid shaft that can poke through the external fabric barrier and escape from your product more easily.

What terms will I run into shopping for down products?

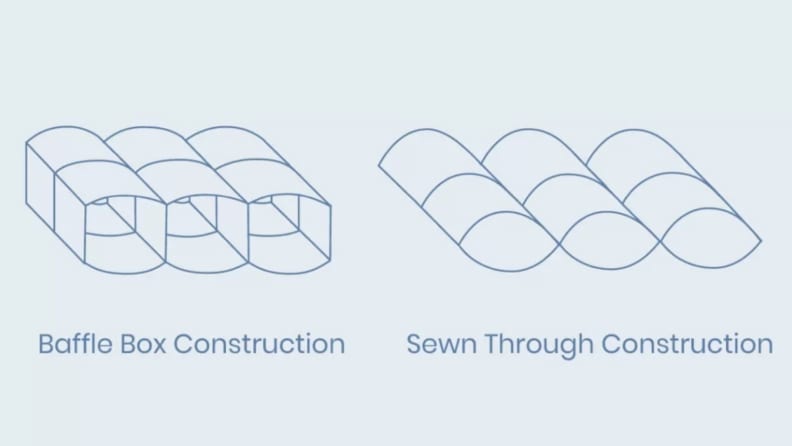

Baffle box construction creates individual compartments which keep down lofty and distributed throughout a blanket.

Thread count is something we’ve all heard thrown around in bedding, but don’t always understand. Thread count just refers to the number of threads per square inch, for duvets and pillows this is in reference to the fabric encasing. When it comes to feather and down filled products, getting a decent thread count—in the 300-600 range—will prevent bits of fluff and feather shafts from poking through and going rogue.

Fill power is a measure of down’s fluffiness, and is specific to products that rely on down for insulation like vests, jackets, and down comforters or duvets. To assess fill power, manufacturers take one ounce of loft (the fill or stuffing itself) and measure how many cubic inches of space it fills. Fill power is measured in the hundreds, and higher numbers generally indicate quality down that will be warmer relative to its physical weight and more resilient to the tests of time. This is because the flufflier the down, the more heat it can trap. Anywhere between 600 to 700 fill power is considered middle-of-the-road when it comes to down warmth and quality. Bedding and clothing items with a fill power of 700-plus are considered warmer, Ueda says. But they often carry a higher price, too.

Sewn through is a construction term you may see on comforters and duvets. It refers to stitching through the two pieces of fabric—in any shape or design—to keep fill distributed throughout a blanket. It will keep the down or down alternative from migrating and clumping all to one side, but because the stitches can go through the fill itself and push it to one side or the other of the seam, it may create cold spots where there’s little, or no, loft, making the blanket less insulating. Down-filled-clothing sometimes uses sewn-through construction as well (just think about the stitching in Michelin-man style fluffy jackets), but it isn’t usually labeled as such on the tag.

Baffle box is a construction and term that’s largely relegated to bedding, and refers to creating boxes that contain the down by sewing narrow strips of fabric inside the comforter perpendicular to the outer fabric. It separates the fill into three-dimensional cubical compartments that allows the down to retain its loft, but also keeps it distributed throughout a duvet. For this reason, baffle-box comforters tend to be more uniformly warm than ones made with sewn-through construction, but they also often run on the pricier side.

Can I check if products use humanely sourced down?

Some consumers may find down-filled options less appealing because it’s an animal product, and where animals are involved, welfare comes into play. It’s impossible to get around the issue entirely, and know your product is perfect, unless you opt for down alternative.

There are three feather harvesting practices: post mortem (after death), gathering, and live plucking. Nowadays most birds that provide down or feathers aren’t raised specifically for their plumage—instead, they’re raised for meat, and the down and feathers are harvested as a byproduct post mortem, much like leather. In this case, birds are generally plucked post mortem. In the gathering technique, birds are still alive but the plumage that’s collected is already loose from the bird’s annual molt—a summer period when they shed their flight feathers in order to grow new ones. It can still be difficult on the bird, as there’s risk of pulling out feathers that aren’t ready, irritating the skin, and catching and restraining a bird is stressful, to begin with. Live plucking is an older practice that’s what it sounds like. It causes suffering for the birds, but is outdated, for the most part. Many companies exclude live plucked down from products.

It’s never easy to know exactly how an animal is treated behind the scenes. There are, however, a handful of certifications and standards that aim to provide consumers insight by giving you a better sense of how down or feathers are produced and sourced, and rule out practices like live plucking in the production of the product. The Responsible Down Standard or RDS (which is offered by the Textile exchange and NSF, more on that below), and the Down Association of Canada’s Canadian Downmark Certification are two of the more common labels. Both ensure down producers don’t use practices like live-plucking. They also exclude down and feathers sourced from force-fed ducks or geese, which can be done to birds raised for foie gras, a French delicacy that’s made from a fattened bird’s liver. In addition to being inhumane, force feeding causes birds to produce lower quality down.

Another less common standard that’s held by a handful of manufacturers, including Patagonia, is the Global Traceable Down Standard from NSF. This standard ensures that products are produced with respect for animal welfare, which is assessed during unannounced audits. “Traceable” means the product’s sources are transparent, and can be followed throughout the chain (e.g. from the parent bird of a hatchling egg to the chick and throughout its life). In the case of the Global Traceable Down Standard, the traceability ensures that a product doesn’t mix down from uncertified sources that may not meet the same criteria or standards.

How do I care for my down or down-alternative product?

Down is known for its warmth to weight ratio.

So you’ve bought an expensive down or down alternative comforter. Now what?

Starting with the basics: Follow tag instructions. On occasion, down products can be washed, but more often than not, they’re dry-clean only. This is because washing in water can take away the down’s fluffiness, i.e. the characteristic that keeps you insulated and warm. However, Ueda says there are some products where she’d be willing to take the gamble. “I’ve washed down pillows and didn’t notice anything, maybe they were a little less fluffy,” she says. “I wouldn’t wash them frequently because over time it will degrade the down, so it’s kind of ‘wash at your own risk.’”

If you buy a particularly warm comforter because you live in a region that has rough winters, storage is another thing to keep in mind. It goes without saying that you don’t want to store a dirty comforter, so be sure it’s clean before you stow it away. Vacuum sealing your down might seem like a great option, but it “can over-compress any comforter and compromise it’s loft for the next use,” Elks says. Both down and down-alternative only have so much resilience, but synthetic fills may fare worse under pressure. Elks suggests storing your comforter in a breathable cotton bag, as it protects from dust but allows moisture to escape.